Editor’s note: This piece was originally published in the Summer 2010 issue of the spectacular Virginia Quarterly Review. On Monday, May 23,the author is giving a reading at 7:00 pm at Valley Bar in Phoenix, Arizona, along with author, publisher, and Arizona State University professor Sally Ball. Learn more…

1.

From the moment we arrive, the departures begin.

Navigating parking, port-a-potty lines. Skirting the hot-dog platters.

Inside Jumbo, the two-hundred-ton cylinder built to house the explosion (a plan abandoned as confidence in the bomb grew), families pose and grin. A girl takes a halfhearted stab at a cartwheel; another mimes skateboarding along Jumbo’s pockmarked metal. My friend and I watch, skim Jumbo’s plaque, wonder if we should head to the McDonald ranch house or walk straight to the site.

At the souvenir stands, there are mushroom-cloud T-shirts, Fat Man souvenir pins, racks of paperback books: bios of Oppenheimer, The Day the Sun Rose Twice; guides to New Mexico hikes and a children’s collection of trickster tales with a smirking turquoise coyote on its cover.

Nearby, a woman beckons us to her makeshift booth. She gives us a hand-typed magenta sheet that allows us to add up our annual radiation exposure. There are blank spaces to complete — How many x-rays and plane trips have I had? How many people do I spend more than eight hours per day with? — but some numbers have already been calculated: ground radiation (twenty-six mrem, it claims, a number, at least for me, severed from any meaning), water and food (twenty-eight), fallout from nuclear-weapons tests pre-1963 (four).

Arranged on her folding table is a seemingly random assortment of things — a clock, a banana, a plate — next to a few samples of Trinitite, the name given to the site’s post-explosion ground cover of fused sand. Each piece looks like a bit of faded coral, or merely a moss-covered rock.

To the gathering crowd, she’ll demonstrate how the dial on her Geiger counter lurches as it hovers over the household items, then barely trembles near the melted soil. But I’m barely listening. I’d read accounts of the bomb transforming this desert to a sea of emerald beads the color of jade. I’m feeling disappointed; the Trinitite is not as luminous as I’d hoped.

2.

We’re standing in a fenced-in field near the center of the crater made by the bomb; it is, in truth, a slight depression in the earth almost impossible to see.

Six bikers pose, arm in arm, at the lava-rock obelisk which marks the precise spot of the explosion; a group of Texans wait their turn.

Some kids run helter-skelter across the desert scruff, arms outstretched, pretending to be airplanes. A family peers into a small spot that has been cordoned off with iron rails in order to see what remains of the vaporized hundred-foot tower which had housed the bomb at detonation — a few sheared-off iron rods jutting up from a patch of lumpy dirt.

At the field’s periphery, some of the tourists walk in a slow stoop, presumably scavenging for Trinitite, pieces of which can still be found. As I watch them, I worry that I’ll never make it back to Santa Fe in time for the wedding ceremony I was supposed to attend. I still can’t even explain why I’m here.

At the field’s north side, there are photographs affixed along the fence. “Like stations of the cross,” my friend suggests.

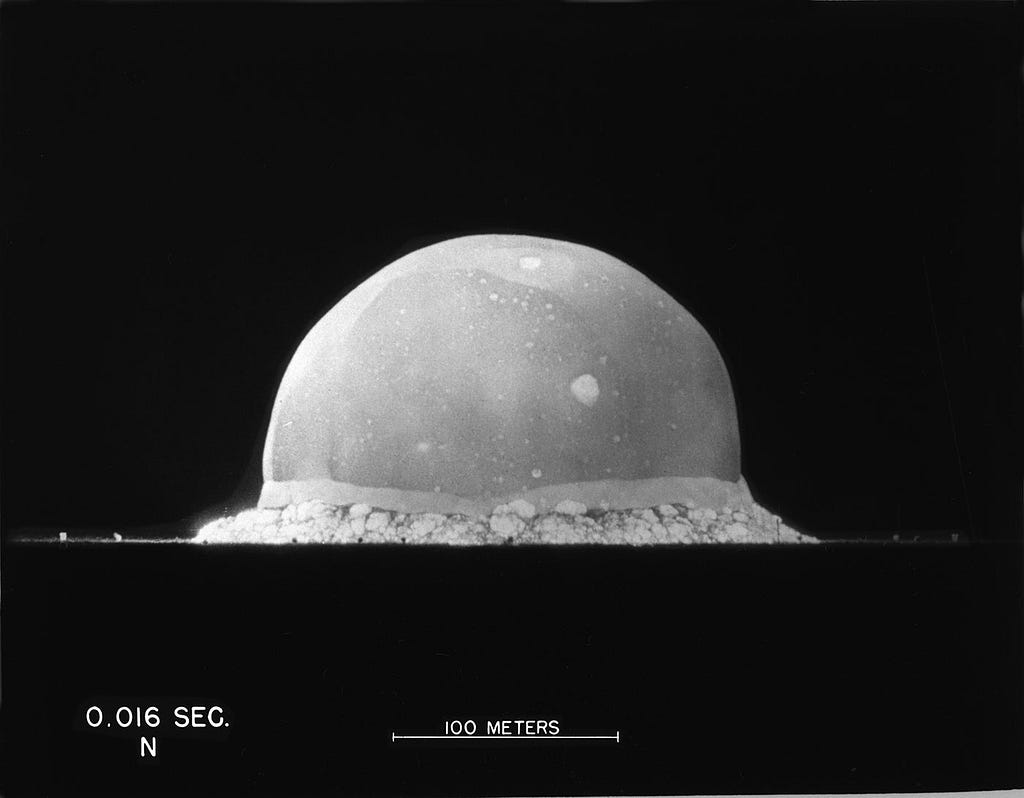

Some are hardly surprising: aerial shots of Trinity base camp, the Gadget being slowly hoisted to the tower’s peak (a few feet from the assembled bomb, a man reclines, almost rakish, like someone lounging along the Coney Island boardwalk), and, of course, those iconic shots of the fireball mere hundredths of seconds after detonation.

Those black-and-white photos of churning light have become so familiar they’re nearly impossible to actually see. Like O’Keeffe’s undulant calla lilies or Hopper’s stool-perched nighthawks, the images have been so frequently reproduced they’ve lost their singularity, and seem instead like any other bit of elide-able Americana. Try to rekindle your strategies of seeing, and they evade through other means, quick shifting like optical illusions: here, the explosion becomes a sunrise; here, the fiery curtain of the debris turns, for a second, into the molten tip on a glassblower’s pipe, then Edgerton’s stop-motion photo of a drop of milk splashing into a saucer.

Who chooses these images we gaze upon, backs to the obelisk, staving off the blankness of the site? And, if the desert’s sun-bleaching heat prevents them from being displayed year round, whose job is it, in the early-morning hours of these biannual open houses, to skulk through the crater and place them at each prearranged spot?

Without the photos to look at, would we be bored here? Would we arrive, then ask, is that all?

Some of these images, as if we needed any help, seem designed to distract from what we’re here to see. One captures the Trinity Site Polo Team “ready for action.” And there’s a shot of men waiting outside the mess hall, eager for the evening’s grub. Although there’s not much to look at — the foreground jeep, a line of soldiers outside a cabin-like building — the caption attempts to detour blandness. Thus we’re told how, during one lunch hour, a soldier named Felix Delpark accidentally flipped a bull snake over the mess hall; when he peered around the corner, he saw men squinting into the sky, wondering if an eagle or a hawk had dropped the writhing form on their heads.

Needless to say — is that what I mean? — there are no shots at ground zero of the Enola Gay, no panoramas of the void that Hiroshima and Nagasaki became. In the world of these photos, the only malignant thing dropping from any sky is a single flailing snake.

Toward the end of this photographic procession, we’re given a portrait of Kenneth Bainbridge, test director, seated in a coat and tie, wielding an impregnable look and angling in his lap, just enough so that we see it too, a black-and-white shot of the Trinity explosion. A glossy photographer’s light radiates behind him, bright as the blast whose image he holds. I watch someone lean in to take a photo of this photo affixed to the fence. Standing at ground zero, he makes an image of the image of a man who holds an image of the blast.

3.

The night before my trip to Trinity, my wife and I threw a dinner party for a writer who was visiting the college where I work. For me, it was a night saturated with distractions: on the way to buy last-minute ingredients for our meal, I crashed our car, rear-ending a woman who had been waiting to merge into traffic. With her window shattered and the back of her Toyota caved in, the driver, after a few moments of shock, lurched from her vehicle with a streak of blood on her face.

I flitted through the night, jarred from the collision, worried about the woman I had hit, but also concerned about what the accident might do to our insurance. I was trying to measure the depth of my wife’s anger over her wrecked car even as I attended to the room’s wine glasses, mulled over the prospect of six hours in a PT Cruiser rental, and fretted over the thickness of a blackish chicken mole bubbling on the stove. All of this was coupled with the brimming certainty that I’d never make it back from my planned trip to Trinity in time for our friends’ wedding ceremony.

Over dessert, one of the guests, a photographer, told me about his own visit to the site some years before. “There’s nothing much to see,” he advised, “but once you’re there, just sit with it.” Said over the dregs of the night, such a moment of reflection seemed easy, inevitable. At the very least. Of course.

Now, though, standing at ground zero, I’m wondering how one begins to contemplate such an event. In the blankness of that space, smack-dab in the bomb’s craterless crater, what is it I feel?

There’s a model of Fat Man parked on a flatbed truck. There’s the striated ridge of the surrounding mountain range, familiar because it serves as the margin-crammed backdrop to those photos of men milling around the vanished tower, all looking closely at what’s no longer there.

Before I’ve even really decided to move on, I’m following a stream of people leaving the crater for the McDonald ranch. I’m gazing at the razor-backed mountains whose name I’ve forgotten, wondering if I’d call them beautiful.

4.

A wind churns up a curtain of dirt, obliterating the view. How can the bus driver even see where he’s going? I try to jot a few things in my notebook, but the washboard road trembles my pen, rendering everything illegible.

Instead, I pull out the stapled pamphlet that had been handed to me as we entered the base’s north Stallion Gate. “Enjoy your visit,” the woman had told us, wind-whipped but smiling in a red wool coat, gesturing with her hand as if welcoming us into a hotel lobby.

Unable to write or lose myself in the landscape, I flip through what’s inside. More summer camp-like photos — a baby-faced sergeant with his arms flung across the sun-warmed necks of two horses; soldiers enjoying a midday swim in the ranch-house water tank — and an accompanying text which lurches from perfunctory information on the Manhattan Project to anecdotes of daily life. Some men confused scorpions with crawdads. Haircuts were given with horse clippers. Some men hunted pronghorn, turning the meat into soup that was, by all accounts, delicious.

Oppenheimer would later claim that he remembered Vishnu in The Bhagavad-Gita — “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds” — and yet gave credit for the morning’s best line to a back-slapping Kenneth Bainbridge: “Now we are all sons-a-bitches.”

Perhaps it’s merely trite to point out government euphemism. Nonetheless, events at Trinity “ushered in” the atomic age, a verb summoning, for me, weddings, flashlights, plush third-row seats; a smile, a red wool coat. Nonetheless, “All life on earth has been touched by the event.” “Touch,” from the Italian, meaning “stroke” or “light blow.”

Nonetheless, Hiroshima and Nagasaki receive a single sentence each, whereas the pamphlet’s entire last page is given over to a drawing of the military patch issued to Trinity personnel. At the page’s bottom edge, there’s a code to guide our understanding. Thus the bolt of lightning descending from a white cloud forms a question mark and symbolizes, we’re told, the project’s “unknown results.” A cracked yellow sphere stands for the atom, and the light-cobalt background on which all of this floats represents — what else? — the universe.

5.

For its first trip out into the world, the Gadget’s two hemispheres of plutonium traveled in the backseat of a Plymouth sedan.

Packed into a waterproof casing, then a shockproof wooden crate, it snaked down the only road leading from Los Alamos, through each intersection of Santa Fe with a wailing blast of the horn, through the Indian reservations and tumbleweed-scabbed hills, past Albuquerque, through Belen (“Little Bethlehem,” where the convoy stopped for pancakes), past the Bosque del Apache’s mud-scavenging ducks, and over the soldier-dotted dirt road that weaves to base camp until it arrived, by six that night, into the converted master bedroom of the McDonald Ranch.

The room had been prepared, sealed with sheets of plastic and electrical tape. Early the next morning, the bomb’s pieces were laid out on an empty table covered with sanitized brown paper. Someone wearing rubber gloves cupped the plutonium and said it felt warm, “like a live rabbit.”

That kind of live pulse is what I expected to feel while visiting Trinity’s crater. Instead, standing on the scarred soil of one of the twentieth century’s hubs, I’d felt only the banal throb of distance and void. A checkmark now that I had visited, after many years of thinking I might.

At the ranch, though, something changes when I step into what was labeled the Plutonium Assembly Room. Despite the thick crowds and near-constant click of disposable cameras, despite the three Greyhound busloads of Cub Scouts — all with matching dark-blue Nuclear Science Merit Badge caps, jostling and cackling their way through the ranch house — when I enter this space something blindsides me. For one tail-spinning moment, a gut punch, a free-fall; a crime scene, a transgression.

Which, given my skittishness around words such as “aura” and “energy,” are feelings, even then, that I want to explain away.

Perhaps it’s the day’s accruing weight; or less abstractly, the accruing wind. There’s the ham-fisted stuff of horror films — the isolated home, creaking wood floors, a single light bulb dangling from the ceiling — and there’s the front door hauntingly repainted with its original scrawl: “Please use other doors — keep this room clean,” as if the Gadget, rabbit-warm, were still somewhere nearby.

And unlike the scale, the light, the sound of that nuclear blast, it’s not hard to imagine the bomb’s assembly: near-steady hands, sheets of brown paper; a few jeeps, as precautions, idling outside.

More than anything, there’s the cramped space itself — a contrast to ground zero’s desert sprawl — where the mind is afforded little breathing room. Here, just here. Instead of a concept, floorboards and walls.

In a poem by Zbigniew Herbert, a man reads a newspaper account of scores of dead soldiers but feels mostly indifference:

they don’t speak to the imagination

there are too many of them

the numeral zero at the end

changes them into an abstraction

Such is, the poem concludes, “the arithmetic of compassion.” For one reeling moment at this ranch house, that room blared something to the imagination, insisting on what for hours had been merely abstract.

And then, even so, what of it? How to translate, and then act upon, what the mind, at long last, grasps? How long are such proximities sustainable? Blocking traffic, watching paramedics snap on pale-blue gloves before dabbing at a woman’s blood-smudged face, I felt dread, the vague thrum of guilt, then wondered if there was still time to pick up corn tortillas. I suspected I should try to speak to the woman I had hit, and then returned to tracing, again and again, the bright, simple shape of the number two stamped on her license plate.

By the time I was through trying to explain all of this to myself — Back on the bus? Somewhere in the Trinity Site parking lot? — I could feel that sense of the unspeakable already beginning to fade.

6.

A different kind of veer: according to one account, as the world’s first countdown entered its final stages, “a local radio station began broadcasting on the same wavelength” and, for a few seconds, the opening strains of Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite overlaid the numbers counting down.

As men smeared on sunscreen in the predawn dark, as a few worried that the world’s atmosphere would ignite, a handful of measures of Tchaikovsky interrupted the inevitable. And then, of course, they were gone.

My reading of this historical footnote fluctuates with my mood. Sometimes, the anecdote affords a reminder of other modes of making. Even if the gesture is futile, let there be, for even a moment, this scrap of music wielded like a clenched fist.

Then again, as Seamus Heaney once wrote, no poem ever stopped a tank, and let’s admit those few bars of confectionary froth halted nothing. The plodding countdown faded to a violin ascent, then returned to its monotone thundering, exactly as it had been before.

Besides, doesn’t the Nutcracker beg for ridicule? If Beethoven had flared across that landscape, most likely this story would be much better known: think of cellist Pablo Casals in Barcelona, determined to complete his rehearsal of Beethoven’s Ninth even as fascist troops descended. What we crave is resilience, artistic magnificence; what we’re given, as a meager, metonymic bone, is music which for me calls forth clumsy pirouettes in a peppermint forest, holiday ads for chicken nuggets.

Which leaves us with merely those numbers counting down.

7.

In a telegram from early July, Oppenheimer announced that “any time after the fifteenth would be a good time for our fishing trip.” And, afterward, he let his wife know that the test had been a success by telephoning a coded command: “You can change the sheets.” A matter of fact, similar to the way some eyewitnesses conjured the event through employing the mundane: The fireball’s skirt. Like opening a hot oven. Like opening the heavy curtains of a darkened room to a flood of sunlight.

Reduction, distancing, explaining away. If one function of trope is expansive inquiry into our world, so much of the language churning out from Trinity serves as a means to diminish, conceal. Fishing trip, live rabbit. Curtains, hot oven, fresh sheets.Gadget, mushroom cloud.

Just after the explosion, some wept, swigged bourbon, or howled with joy before falling, as if on cue, into a snake-line dance. A man said the war would end soon. A rancher, many miles from the site, was thrown from his bed and asked, “What the hell was that?”

As the bomb was detonated, the Italian physicist Enrico Fermi began dropping small pieces of paper. In that windless morning, the waves of the blast pushed his scraps two-and-a-half meters from where he stood, allowing him to quickly calculate that the explosion was equal to ten thousand tons of TNT.

Oppenheimer would later claim that he remembered Vishnu in The Bhagavad-Gita — “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds” — and yet gave credit for the morning’s best line to a back-slapping Kenneth Bainbridge: “Now we are all sons-a-bitches.”

8.

In his youth, Oppenheimer summered in New Mexico, slow-wandering the Pecos mountains on horseback, sometimes losing himself in the wilderness for days. When he chose Los Alamos as the place to develop the world’s first atomic bomb, he also found, by his own admission, a means to circle back to a landscape he loved. Paradoxically, when he helped decide that his new weapon would be tested in the state’s Jornada del Muerto (from the Spanish: journey of death), that same beloved desert — with its barren miles of yucca, mesquite, and roaming antelope herds — was declared merely a void.

Although his geographical preferences were clear, Oppenheimer claimed he couldn’t fully account for naming the site “Trinity.” Some historians, scouring for explanation, have strayed back to Hinduism’s interlocked gods of preservation, destruction, and creation; whereas Oppenheimer himself guessed he might have had in mind John Donne’s Holy Sonnet that begins “Batter my heart, three-person’d god.”

Forgive me for asking the obvious, but does not the name Trinity stem from the act of playing god in the desert?

Besides, one wonders, why would anyone need to plunder Renaissance poetry in order to latch on to one of Christianity’s most basic tenets? The idea is already well within reach.

And yet, we depend upon that circuitous route to more clearly reveal Oppenheimer’s mind, and thus trouble the image of the man in his porkpie hat, back at base camp after the explosion, stepping from his car with a High Noon strut. After all, his alibi poem is one which resonates far beyond a nod to the Christian Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. In that sonnet, violence is the only path toward salvation, the only means by which wholeness can be restored. Unable to know redemption and grace through gentler manifestations of the divine — a slight knock, breath and light — the speaker begs to be struck and lashed by God. “Break, blow, burn,” he commands.

Now we’re getting somewhere.

9.

Enrico Fermi, who had placed side bets on whether the entirety of New Mexico would be incinerated by the blast, who planned to beeline for ground zero in a tank in order to examine the debris, and who made calculations of the blast’s force even as the explosion lunged around him, was unable to drive after the Trinity test.

Sitting behind the wheel, it felt, he said, as if there were no straight stretches of road. Instead, the car leapt from curve to curve.

Nowhere else do we have a sense of the explosion’s effect on one of its central architects. The mind, like the road, swerves and swerves, unwilling to accept what it’s seen.

Perhaps nothing speaks more to a human resistance to violence than these contorting, spring-boarding leaps. The mind twists and writhes, wrenches and veers, something like a fish trying to escape what’s lodged in its lip.

Or perhaps this, too, is yet another swerve. A means of evasion. Of slipping off the hook.

10.

To say that my friend and I were speechless during some of the drive back — both of us, in our way, “sitting with it” — would be true. But, again, what of it?

Whatever it was we were feeling — awe, a whiff of terror, something else I doubt we could name — eventually gave way, as it often will. Idle chat. Antelope signs. Soon enough, I-25’s straight shot north, cruise control locked in.

It doesn’t really matter how we filled the time — suffice to say we filled it. We talked, stopped for a burger, and, many blurred miles later, I dropped him at an airport hotel — to brood, he insisted, and drink red wine, and watch anything on TV with cyborgs. Soon enough, I was alone in the car.

And, finally, I could try to fathom the numbers. 14,000 degrees. 200,000 dead.

And yet, just as ground zero manages to keep the parade of zeros far from our minds, I can’t pretend, during the silence of that drive, that I held any facts at the ready. Our means of evasion, besides, don’t rely on numbers, or any single device: the tourist belt-notch; all those miles to Nagasaki; the time, some believe, the bomb shaved off the war.

You stand in a field that seems to be nowhere; your mind clambers off to other things.

I’m an hour away from the Mustang Room at the Cowgirl Hall of Fame, where I’ll hear — over applause as the bride and groom strut in — the best man humming “Ode to Joy,” golf jokes in the guise of marriage blessings, blasted ’80s pop hits by Wham! and Human League. I have little more than an hour to sit in silence when my thoughts, it’s true, flitter back to the site. But I’m thinking, too, of a story my father used to tell about Oppenheimer — where did he get this? — strapping a bottle of vermouth to a rocket, then thrusting his gin glass out the window in order to make the world’s driest martini. I’m remembering a few peak-season twilights at the Bosque del Apache observation deck as sandhill cranes soared into a sun-bronzed lake, and I’m adding up, hour by hour, tonight’s babysitting fees. I’m skidding back to the car crash’s sickening crunch of metal, and already savoring the detail of those scuttling cub scouts, the chance metaphor of bus windows blocked by dirt. In a rental car, whipping back through desert hills, I recall, out of nowhere, that mountain range’s name — Oscura, from the Spanish: unknown, obscure. The name struck me, even then, as something that mattered.

Matt Donovan is the author of two collections of poetry — Vellum (Mariner, 2007) and the chapbook Ten Burnt Lakes (Tupelo Press, forthcoming 2017) — as well as the collection of essays, A Cloud of Unusual Size and Shape: Meditations on Ruin and Redemption (Trinity University Press, 2016).