In Hollywood, the future of transportation tends to be glamorous, gee-whiz, and high-tech. And that’s no huge surprise, since many movies about the future have lucrative luxury car sponsorships. Hence the zooming magnetic Lexus in Minority Report (2002) or Will Smith’s very aerodynamic Audi in I, Robot (2004). Indeed, the films featured in big-budget movies (check out the video compilation above) represent important ways that we like to imagine getting around in the future, from sleek personal cars to highly efficient public transit.

But in futurism, there’s a deeper tradition of suspicion of transportation technology and infrastructure. Because who likes getting around, right? We really just want to get where we’re going, where the truly exciting futuristic things are happening. In his visionary nonfiction book Anticipations, from 1901, H. G. Wells begins his painstakingly thorough account of the future with an essay on transportation. It’s the first and most boring chapter in the book, which predicts a one-world government and the death of all but four languages. For Wells, a robust transportation system is fundamental for the growth of cities and the advancement of knowledge and commerce. It’s a grimy business, and not very romantic, so he starts there. It’s absolutely necessary, but he wants to get it out of the way so he can hold forth on the truly interesting stuff about sex, science, and war.

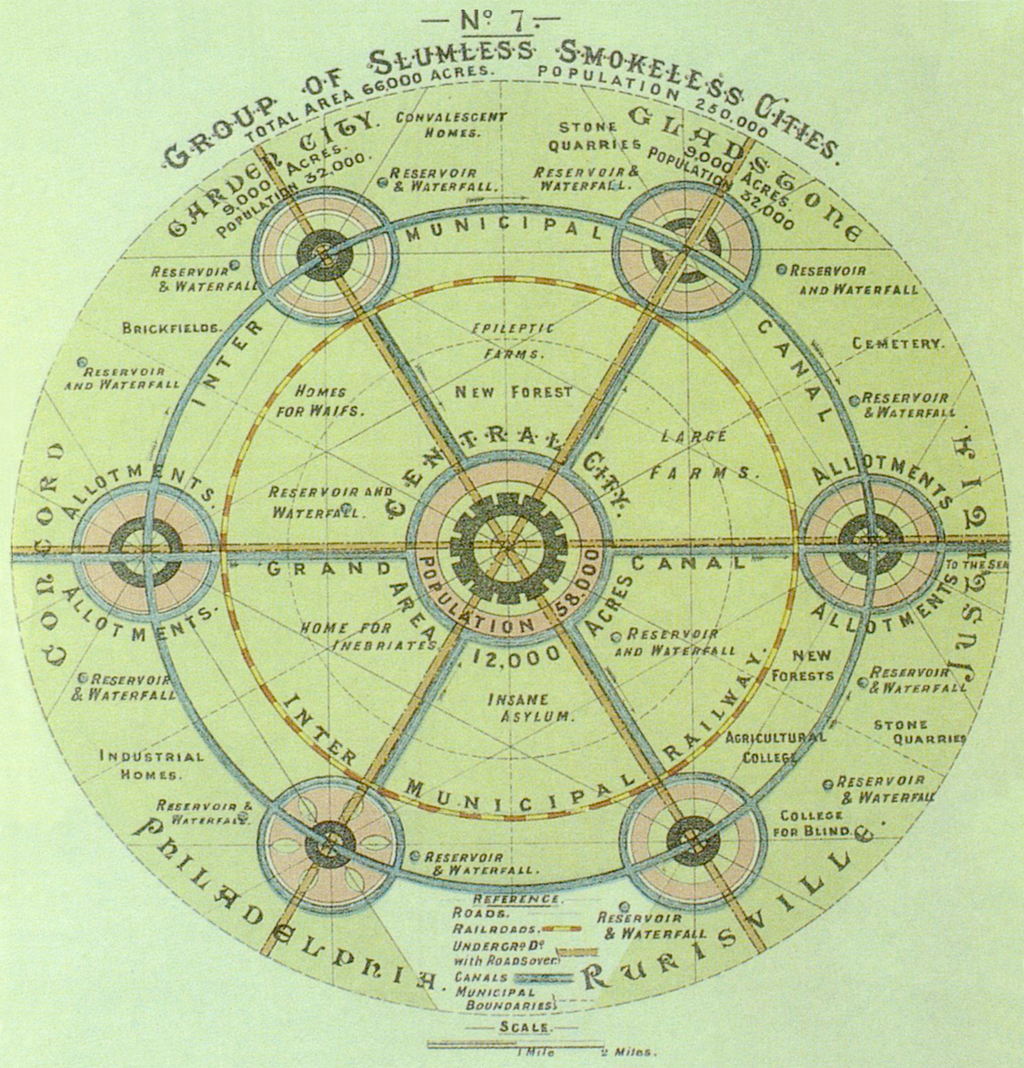

Preceding Wells by just a few years, in 1898, the British bureaucrat Ebenezer Howard proposed the Garden City: a model for “slumless, smokeless” communities designed to eliminate the social ills of increasingly dense, dirty, and socially stratified cities like London. Howard designed the Garden City to balance the convenience and vitality of urban living with the charms and healthful properties of the countryside. Howard was a social reformist but decidedly not a socialist, so he saw this more pleasant city as a solution for escalating tensions around economic inequality. The Garden City is a series of concentric circles. It features roads radiating out from the city center, an encircling railway, and high-speed rail connecting various Garden Cities to one another.

So there is transportation infrastructure, but Howard’s vision was that it would be unobtrusive. Garden cities are compact and walkable, with wide, clean streets, and pedestrian thoroughfares segregated from road and rail lines. They feature oodles of public space, including verdant parks and a giant covered “crystal palace” of arcades. The circular design makes forests, farms, and waterways easily accessible by foot. It’s a city designed to reduce transportation time. Howard segregates transportation infrastructure from living, shopping, and education spaces. He untangles the mish-mash of different vehicles and people crowding London’s narrow streets. It’s tidy; everything is in its own place. This gives the illusion of a countryside lightly dotted with human inhabitants. Think the Shire from The Lord of the Rings, if it was planned by someone obsessed with geometry.

Ten years earlier, in 1888, Edward Bellamy, a socialist from Massachusetts, published his utopian novel Looking Backward. Bellamy’s vision of the future is quite different than Howard’s. Bellamy was a Marxist with a deep faith in the power of technological ingenuity and rationality. He didn’t share Howard’s Emersonian love for the countryside. But his vision of Boston in the year 2000 also tries to cure the maladies inflicted upon cities by industrialization, rapid growth, and poor planning.

Bellamy basically avoids talking about transportation entirely, although he lavishes attention on nearly every other detail of life in his technocratic socialist utopia. There are trains, and wide streets, like Howard, but Bellamy’s vision really doubles down on walkability, with neighborhoods designed so that work and shopping and schools are all within 5 or 10 minutes. Walkability is so important to these future Bostonites that they deploy a full-sidewalk, all-encompassing rain canopy anytime the weather turns bad. When people shop, they visit their neighborhood warehouse, place their orders, and have their packages delivered home almost instantaneously by pneumatic tubes that snake underneath the city and into the surrounding countryside. Bellamy, with his puzzle-box mind, seems to find them much more rational than cars and trains and buses.

So in both Howard’s English-village vision and Bellamy’s slick, rationalist vision, transportation infrastructure is pushed to the side, or underground, or transmuted into tubes. Meanwhile, their contemporary H. G. Wells tells us how important it is, but tries to get past it as quickly as possible. Like all of us, they’re just trying to get where they’re going, and they don’t want to prattle on for too long about how.

This line of thinking persists through the mid-20th century. In 1962, Lewis Mumford published The City in History, which won the National Book Award and continues to shape conversations about urban planning and architecture today. Mumford was a friend of the architect Frank Lloyd Wright and of Clarence Stein, who actually popularized the Garden City idea in the U.S. In 1958, Mumford wrote, “The purpose of transportation is to bring people and goods to places where they are needed, and to concentrate the greatest variety of goods and people within a limited area, in order to widen the possibility of choice without making it necessary to travel.”

Today, this focus on reducing the time and complexity of transportation is still relevant. In 2013, Tony Hsieh, the CEO of Zappos, moved his company’s headquarters to the dilapidated urban core of Las Vegas. He vowed to revitalize the area as a cultural and economic hub — and importantly, as a walkable hub in the midst of a city suffering from extremes of urban sprawl.

Meanwhile, top real estate websites like Zillow and Redfin use algorithmic “walkability” scores to help buyers find homes in areas where they can avoid using cars and public transit. We’re still mostly a car culture, but the traces of these dissident futures from the turn of the previous century are with us, and they might even be surging back to the forefront.

It’s hard to think about transportation machines as exciting, really, if you think about it. Sure, in road trip movies, cars and trains are machines for self-discovery and adventure. But on a day-to-day basis, transportation time is just friction, lost between the places we want to be, the things we need to do, and the experiences we want to have. If we all suddenly had Blade Runner’s flying cars, it would be a week, or a month, or maybe a year, before we started getting bored of them, and figuring out ways to automate them, or avoid them entirely. And this is something that Howard, Bellamy, and their contemporaries would have understood all too well.

This piece is adapted from a talk originally delivered at Future Tense’s “The History of the Future” event in Washington, D.C. on November 14, 2017.