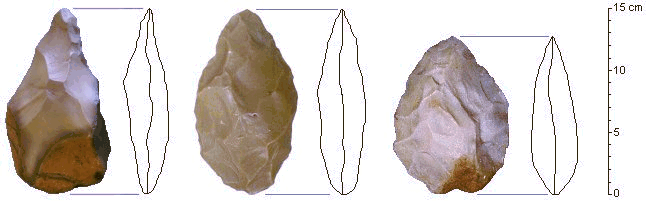

Behold the Acheulean Hand Axe — among the earliest Paleolithic stone tool technologies. These were conceived and crafted by ancestral hominins — upright bipedal primates — some five hundred thousand years ago.

These creatures were not people, not Homo sapiens. They looked like long-legged walking apes with small heads. But there they were, benefiting mightily from first generation handheld mobile technology. These tools offered great advantage to an otherwise meek creature — a precarious ape on two legs with no fangs, no claws, no clothes, no Wi-Fi. Advantage enough that the v7.5 of the hominin model single-handedly inherited the whole Earth, ushered in the Anthropocene and effected massive climate change. When the first Homo heidelbergensis hunkered down and chipped out the first hand axe, the gods on Olympus observed a moment of silence.

I know, I know — these tools don’t seem all that impressive. While they may look primitive, generations of archaeology grad students have learned the hard way that crafting these tools requires precise instruction, manual dexterity, and hundreds of hours of practice. And brains. Experimental archaeologist Dietrich Stout of Emory University has been scanning human brains as they knap these stone tools. His data indicates that Paleolithic stone tool manufacturing relies heavily on areas of the brain associated with plasticity and culture. More specifically, chipping a chunk of obsidian into a specimen of five hundred thousand-year-old technology draws on the same frontal and parietal regions of the cortex that govern cognitive control, anticipation, and mimicry. These regions are not nearly as robust in our closest living relatives, the chimps.

Stout’s work indicates something significant. The hypothesis: that natural selection for tool-making ability favored the neurological features that enabled the evolution of language and culture as we know it. It seems our species evolved hand-in-hand with tools; our very neurology and capacity for culture is a direct result of our deep reliance on technology. Stout refers to our species, therefore, as Homo artifex: Human the Skilled Maker of Things. H. artifex is not simply a thinking animal using tools. Our central nervous system is genetically coded to make and utilize. Human and tool overlap completely. We are fused with our technology and have been for millions of years. Homo artifex, therefore, is a cybernetic organism, an evolutionary fusion of tech and flesh. H. artifex is cyborg.

Our tools have evolved as well. Contemporary descendants of the Acheulian Hand Axe like brain-computer interfaces, algorithms, and artificial intelligences extend our cyborg heritage. But there is this: while the Paleolithic hand axe entered our evolutionary neurology, some of these new technologies are evolving neurologies of their own. Take a copy of the journal Neural Computation on a road trip with Watson and see for yourself.

Right now, interfacing with the algorithms in our everyday lives is a bit awkward. We’re often tasked with thinking like our machines in order to use them. But this is changing. These machine intelligences will be humanized. We will teach them poetry and read them stories. Computer scientists like Mark O. Riedl and Brent Harrison at the Georgia Institute of Technology are hoping to enculturate AI by literally teaching it human stories. Our stories encapsulate our values, so exposure to them may be able to teach a bot to delineate (and express) culturally expected behavior versus pathological behavior. In a fascinating paper for the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, they demonstrate how an intelligent entity may reverse engineer stories and extract the tacit value systems of the culture that originated them. Such an entity, they hypothesize, “can learn what it means to be human by immersing itself in…stories.” Similarly, Facebook is reading children’s stories to their algorithm, thereby teaching it to anticipate and rapidly replicate the structures of natural language.

These machine intelligences are in their infancy, reading stories on our laps and learning games at recess. But they will grow up and become more human as they mature, fusing lessons from our flesh to their machine manifestation: Artifex homo. Science fiction at our doorsteps. Perhaps that little piece of Cylon folk wisdom is spot on: all of this has happened before and will happen again.

Will Homo artifex be met in the middle by Artifex homo? Cyborgs all, will we recognize each other there?