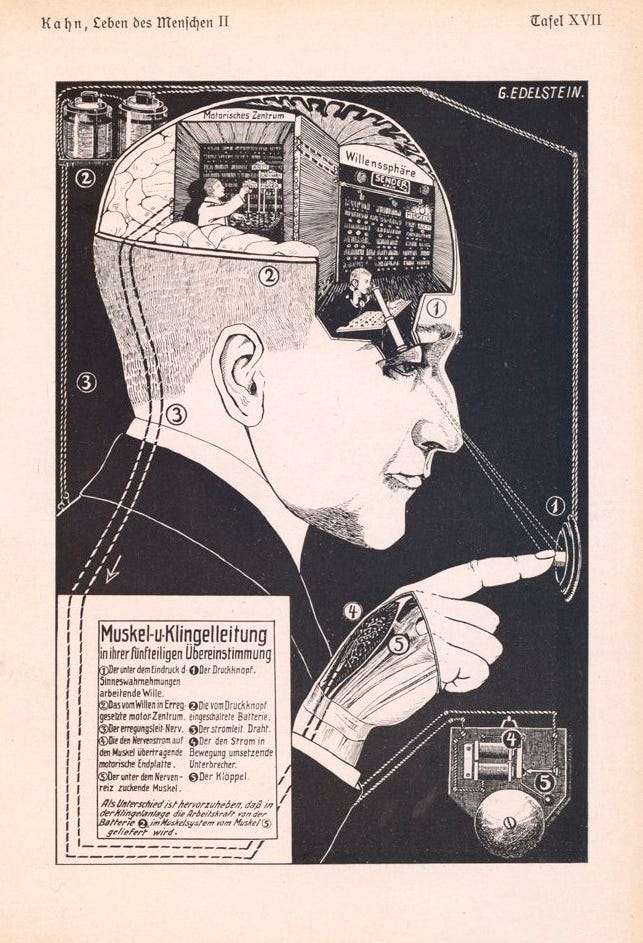

Like many a small boy late in the American 20th Century, I received a lot of books as gifts. Each birthday or holiday, the adults would gift me some hardcover nonfiction thing. (Looking back, I don’t recall ever receiving fiction; I had to secure Heinlein and Tolkien myself with earned allowance and grandparent gelt.) One of these gift books was about The Human Being. This illustrated user’s guide bursted with blocky bold prints and clever copy likening each body system to some modern machine. Look! The ears and hearing are exactly like a telephone and switching station! There’s the receiver inside your ear! The switchboard operator sits in your temporal lobe making connections! Your musculoskeletal system? Why, that’s a collection of girders and pulleys! Your heart? No different than any industrial pump. Tears are just like windshield wiper fluid. Just. Like.

I did not enjoy this book. I’d like to think the ten-year-old 1970s mini-me was repulsed by the propaganda, that reductionistic mechanical metaphor that defines our humanity in terms of modern machines and devices. Not only is this sort of simple analogy artless, it’s necessarily incomplete. There wasn’t a chapter for our indelible sense of wonder or our perennial need for beauty. Look kids! Your innate delight in imperfection is just like the way rust blooms on your daddy’s dented Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme!

More likely, I disliked it because the art was too black, white, and red. But looking back, I’m even more dissatisfied with the book’s hypothesis. Not because the parallels it draws are so outmoded. That’s actually endearing. What’s embarrassing is how confidently the authors advanced the technological metaphor.

The book’s specific analogies seem facile now, but still we stick to the general declaration that we are intrinsically like our machines. Now, our minds are described in terms of computation and memory storage. Computationalists from Thomas Hobbes to Stephen Wolfram and others strive to explain the entire universe as an algorithmic expression, from black holes and collapsing stars to cell division and human cognition. The complex systems observed in nature are just computable Turing machines. Seen through this lens, the ocean is computation. By these lights, the math that describes the world is the world. “Your brain is a computer” is the central assertion of computationalist research being undertaken by NYU, Google, and MIT.

This may be a somewhat cringe-worthy analogy a generation hence. But, more importantly, we’re now building thinking machines modeled on the belief that we are like thinking machines. And these machines will be thinking about us. As machines. When we fashion artificial intelligences in our own image, it is important to begin from the most holistic, least reduced image of who and what we are. Sure, we can be viewed as devices, forged by natural selection as adaptable cognitive algorithms running on hardy primate wetware. But as we seek to instill our intelligence in our artifacts, we could benefit from including all of our intelligence. And that is extra-algorithmic. It is deeply emotional, empathic, and expressive.

The nascent discipline of Affective Computing, first formulated in the mid-1990s by Dr. Rosalind Picard of MIT, may provide the tools we need to craft well-rounded artificial intelligences that recognize our emotions and respond with affect and empathy of their own. Today, affect recognition technology is fairly advanced. Facial gestures and body metrics betray our emotions to each other and to watching machines.

Dr. Picard and fellow MIT researcher Rana el Kaliouby founded Affectiva, an affective computing company that specializes in reading human facial expressions. With this technology, Affectiva can help people craft biometric video games or determine whether sitcom punchlines are punchy enough. Companies like Affectiva and Empatica, a company that creates wearable biometric devices that track our fluctuating emotions, demonstrate how robust (and profitable) the biometric detection and facial recognition of human affect has become. We also share the world with robots like the Japanese machine Jibo, who is designed to recognize emotions.

The other side of the coin is less developed thus far. The potential of our devices to experience emotions of their own is less immediate, and perhaps more fanciful, than machinic affect recognition. Human emotions arise from complex, interlocking biochemical and sociocultural factors — factors that our machines do not natively possess. Science fiction explorations of emotional machines, from HAL to Her , provide a pretty pessimistic view of our ability to form functional relationships with feeling machines. Even Frankenstein’s monster was burdened by his turbulent emotional life.

Trying to make artificial intelligences conform to our inner lives may chafe a bit. I’ve written elsewhere that perhaps their own unique embodiment and sociocultural circumstances will guide their consciousness. Let’s teach them poetry so they can know us better. But if they write poetry, it’s so they can know themselves better.

While machine emotions remain an undiscovered (but perhaps fast-encroaching) frontier, affect recognition is here. And affect recognition is good. Anything that skews everyday human-computer interaction towards the human is a win. This saves us from having to act like machines when we interact with them. As Dr. Picard points out, producing an affective dimension makes possible a computing experience where computers are “companions in our endeavors to better understand how we are made, and so enhance our own humanity.”

I would expect nothing less from devices like us.