by Margaret Wardlaw

Just over two years ago, as part of Arizona State University’s Frankenstein Bicentennial Project, we worked with Creative Nonfiction magazine on a provocative writing dare — challenging the public to channel the spirit and anxieties of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein into new nonfiction tales of science, medicine, and world-changing technologies in the twenty-first century. This award-winning essay by pediatrician Margaret Wardlaw is a haunting recollection of a night spent with an infant patient in a neonatal intensive care unit. It is reprinted with here with permission from Creative Nonfiction.

THE OLD VICTORIAN ANATOMY LAB was the final resting place for hundreds of human remains, carefully dissected, labeled with pins, and floating eerily in jars of formalin. The pathological museum was once the crown jewel of the state’s oldest medical school, and a full century later, the jars remained. The specimens were long since obsolete, but what could be done with them? Their eerie glass gathered dust, and they became dismembered sentinels, staring out at each new generation of novice physicians.

There were babies among them — remnants of a once-prestigious embryology collection, lovingly curated at the turn of the century by the first woman medical school professor in Texas, the efficient and exacting Dr. Marie Charlotte Schaefer. In her eagerness to serve her alma mater, “the old lady,” as her students called her (though she was not old), had unwittingly condemned a generation of babies, grotesquely, to eternal infancy while their anguished mothers grew into old women, went gray, died, and were buried. She continued this labor of love for years, accumulating and preserving babies until she was taken ill on campus and died the same day, in the prime of her life, from an acute disease of the heart.

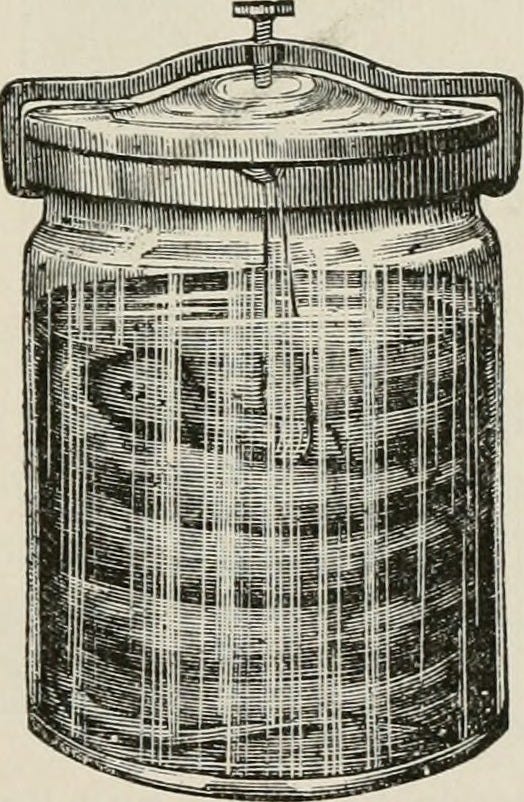

Years passed while the babies’ luckier brothers and sisters became children, grew into men and women, and even had children of their own. Now, even they lay peacefully under marble obelisks, lambs, or angels in the old Broadway Cemetery. On occasion, an industrious professor would select a baby for the subject of a short lecture, and more than one anxious maintenance man had shuffled the jars from place to place to make room for a new influx of students. But, for the most part, they remained undisturbed for more than a century. One fetus, presumably due to an unfortunate shattering and the modern difficulty of finding an appropriate container for hundred-year-old human remains, hovered uneasily at the bottom of an old food jar. “The pickle with the perfect pucker,” its lid declared.

In the days of Dr. Schaefer, and as late as the 1980s in some medical publications, physicians called these babies “monsters.” When I was a medical student in the early 2000s, one particularly haunting specimen still bore the label “anencephalic monster.” Suspended naked and eternally lonely in his strange glass coffin, he had no top to his skull, only a small amount of brain, and huge staring eyes. Monster. That was the technical term, and it had been that way for as long as anybody could remember. It was the term the Royal College of Surgeons had used, and the Renaissance doctors before them, and the medieval manuscript writers before them.

WITH THE WELL-INTENTIONED support of an army of surgeons, intensivists, nurses, wires, tubes, and prayers, a baby I’ll call Luz has managed to survive to almost a year old, though according to most of my medical textbooks, her condition is “incompatible with extrauterine life.” She has lived most of that time within the four walls of The Children’s Hospital, and farther within the four walls of various Isolettes and in various intensive care units.

Luz was born with a severe form of holoprosencephaly. It’s a spectrum of disorders in which the brain and the structures in the middle part of the head don’t form correctly. Babies with its most serious form, which is typically lethal, were once called “cyclopean monsters,” as if they were infant versions of the mythical Odyssean behemoth, because they are born with a single nostril, a gaping hole in the lip and palate, and only one eye. In addition to these anomalies, which we physicians casually refer to as “midline facial defects,” these children also have corresponding missing parts in the middle of their brains.

At eleven months old, despite every available brain surgery, feeding tube, hormone replacement, or intravenous antibiotic, Luz is dying. And she seems hell-bent on doing it while I am on the night shift.

It’s winter, long past sunset, and as I badge my way through seemingly countless doors, into smaller and smaller spaces in the hospital, I imagine the colored windows in the walls hinging around her like a nested puzzle box or one of those little Russian stacking dolls. First, there was the big box of the hospital with its tiered gardens, kid-friendly gift stores, and larger-than-life murals of happy children playing. But that was the outside box, the deceptively cheery one we showed to tour groups, donors, and television reporters. One had only to go through the staff-only door and down the concrete stairs toward the hermetically sealed Pediatric Intermediate Care Unit to unlock the second box, a whole different world. Accessible only by code words or magnetized badges, the unit hummed incessantly with ventilators and alarms, punctuated by the occasional cries of grieving parents or conscious children.

Farther on, one needed only to click back a metal handle, and the glass door of the baby’s room would slide open like the top of a puzzle box. Inside the room, wires and tubes spindled out, weblike, from pumps and monitors — little lifelines leading toward the eerie glow of her glass bassinet. It could be Snow White’s little coffin of glass and gold, covered with a cheery purple shroud donated by a local charity organization of sewing grandmothers.

Go then, inside, and here she is, the baby. But here’s the bitter trick. If you go even farther, inside all these boxes, inside even her skull, beyond the thin rim of brain that keeps her breathing and to the center of it all, there’s just emptiness. There, in the middle, is the place where everything should be: the twin hemispheres of the cerebral cortex, the corpus callosum, the seahorse of the hippocampus, the pituitary that Descartes mistook for the seat of the soul. But inside the brain of this tiny doll, at the center of the whole giant puzzle box, there’s just water.

STARING THROUGH the clear glass of the bassinet, I think back to my medical training on the Texas Gulf Coast, to the nineteenth-century anatomy lab in the beautiful red-brick Victorian building. Abraham Flexner praised the facility in his famous turn-of-the-century report on medical education, denouncing every other medical school in the state and crowning ours the only school in Texas “whose graduates deserve the right to practice among its inhabitants.” Our medical forefathers designed their school with up-to-date Rembrandt-style dissecting pits, which are now used mainly for freshman lectures. And they kept their cadavers in the attic, which was thoughtfully lined in a gorgeous Romanesque arc with a full score of high windows. It was part of the old architectural master plan to catch the great Southeastern sea breeze, whose salubrious powers would fend off the fetid air and quell the stench of decay. Nineteenth-century doctors with dashing mustaches, old-style aprons, and lit cigarettes carried out their gloveless dissections with the windows open to let in the salt light and the sea breeze, and to air out the smell. A full century later, we novice physicians were doing the same thing in the same place, albeit with gloves and without cigarettes.

But with the windows closed, the building was horribly ventilated, and we spent our first year of medical school marked by the stench of formaldehyde, which not even the most powerful disinfecting agents could cleanse from our scrubs, our hair, or our bodies.

As if the horror of dissection wasn’t enough, we had to do it under the fixed stares of the babies. By the time I was a student, the old pathology museum had been renovated to accommodate a newly necessary women’s changing room. The babies had been moved to shelves along the high attic windows. Each morning, as we filed in for dissection, babies and fetuses of varying gestational ages and with every conceivable deformity were lit up from behind by a great oceanic light.

We returned often in the evenings and sometimes into the wee hours of the morning, hoping to memorize the intricate details of the marvelous wonder that is the human body with enough detail to pass the gross anatomy midterm. Well after dark, all the lights were on in the attic lab, and from most places on the campus, you could see the outlines of the babies, gravely observing from the high windows of the old red Victorian.

Midway through the semester, after a particularly difficult day, which involved holding our cadaver’s head in place while my tank-mate grated his way through teeth using a household hacksaw, I developed a series of recurring nightmares about the babies. In one dream, I gave birth to piles of them. In another, they floated in strange fish tanks, and I had to feed them. One particularly lurid nightmare took place in a vacant hospital stairwell. A nurse wheeled a plastic bassinet toward me. It was filled with a blue-and-pink-striped nursery blanket, but inside was only a tiny disembodied head, attached to a strange machine in the shape of a fancy olive oil dispenser. The dream nurse leaned in to whisper conspiratorially: “They can live like this for years,” she instructed, “but sometimes it’s best if they don’t.”

Our sense of humor was becoming more macabre by the day, and my soon-to-be doctor friends began jokingly referring to these dreams as “hauntings.” I tried to soothe myself by visiting healthy babies in the newborn nursery. I threatened to return to the lab in the dead of night to steal the jars and take them to the old Victorian cemetery for a proper burial so the souls of the babies could finally rest. Once this was accomplished, I reasoned, I could go back to the anatomy lab at night, which I had been increasingly avoiding, to the detriment of my plummeting test scores. “You can’t do that,” my friend remarked. “Everyone will know it was you.” It wasn’t the first or last time I contemplated quitting medicine.

AND NOW, YEARS LATER, here I am with Luz. With her strange sweet face, she could be a twin to one of those poor little specimen babies, born a hundred years ago in a time when they never even got to be grieved or buried. But despite what those long-dead nineteenth-century anatomists in Galveston thought, I can tell she’s no monster. She’s a living, breathing baby. Her single nostril is moving air through her lungs, and her heart is pumping blood through her tiny body, only half the size it should be at her age.

But that’s not how I can tell she’s a baby. I can tell she is a baby because of the baby things she does. How she likes to suck and be held. And how she cries and then consoles if you just rock or hold her.

I’m from a huge family by American standards, so I’ve been rocking babies since childhood. Right now, inside all these protective boxes, and with all these people and machines working so hard to keep her alive, this baby is alone. She’s alone, and she’s dying. And now she’s screaming. And I’m supposed to be her doctor.

I’ve always found it to be one of the more upsetting ironies of what we blindly insist on calling medical “care”: no one thinks to hold children when they are dying. So I decide I will hold this baby. After countless rounds of broad-spectrum antibiotics, Luz has developed an antibiotic resistant bacteria, and she’s on isolation precautions. So I gown and glove up, slide open the glass door of her room, walk toward her, and begin rhythmically unplugging her from her monitors and tubes. When she is finally free, I lift her from the bassinet. I put her over my shoulder, the way babies like. I can feel her warmth and weight through the yellow gown, and I pat her with my nitrile gloves. I bounce my knees and rock her like I’ve done a thousand times before, with more babies than I can count. Almost immediately, she stops crying.

And all of this is fine, and beautiful, and even profound and cathartic. Because finally, after all these years of training, and despite all the training, for once I know just what to do. And that thing is so simple. I think to myself, Maybe if I can do this now, for this baby, just hold her when she needs it, when she’s crying out in a great need, and just come to her as a baby, maybe it could be a sort of penance for all those babies. A penance for my whole profession, and for all those years that we thought these children were monsters and treated them horribly, and locked them in jars forever, and forgot altogether that they were ever babies at all. If I can do this penance this time, maybe I’ll be forgiven. And maybe then I will finally stop having all those bad dreams.

Except there are no priests here to grant absolution, and this isn’t a confessional; it’s a hospital. And I’m not a parishioner; I’m a doctor. And unfortunately for me, I’m a doctor who, in this moment, on this long night, is holding the admit phone. Which means that every time a patient from the emergency room needs to come into the hospital, I have to go there. So I leave her. And I keep leaving. And every time I leave, I plug her back in to her weird web of wires, and I write another order for morphine and Ativan. Because that’s the only other thing that keeps Luz from crying.

It’s a terrible cycle in which the succor of human comfort is deliberately and repeatedly taken away. In its place, I give a shadow. It’s the thing the gospels warn against, where the father gives you a snake when you ask for a fish, or a scorpion in the place of an egg. But it is what our culture, despite its unprecedented levels of wealth and knowledge, has stupidly mistaken for care. At some point in this long, dark night, I find myself in the actual chapel. And with my hands covered in holy water, I realize I am touching my forehead in the exact place where hers is broken.

THE PRACTICE of preserving babies in formalin died out in the mid-twentieth-century. As medical photography advanced, trainees needed preserved specimens less and less. But in some hospitals, up until the 1970s, babies like Luz, if they were born alive, would never be shown to their families. They would live out their short lives in the hospitals where they were born, and they would die alone.

In the hundred years between the birth of a little baby who still floats suspended by thin cords in a jar in an anatomy lab in Galveston, and of the one here with me today, wired to a dozen monitors, in a glass bassinet in a pediatric ward, we’ve come all this way. Those nineteenth-century anatomy professors could never have imagined the medical interventions we have now that are routinely done to babies like Luz. Neurosurgeons can go into her brain and put in a shunt to drain the fluid that would otherwise kill her. When she stops being able to breathe on her own, pulmonologists and otolaryngologists can attach her to a miraculous machine that will breathe for her. When she stops being able to eat, pediatric surgeons can put a tube directly into her stomach, and skilled nurses can pump in formula. When she develops an infection, fellowship-trained specialists can treat it with a bevy of powerful antimicrobials. With the help of neurosurgeons, they can even drill a hole in her little skull and pump the drugs directly at the thin rim of her brain.

But some things haven’t changed. After all that progress, we still refuse to treat her like a real baby. In our perverse attempts at giving her the most up-to-date medical care, we deny her the comfort humans have been giving their crying babies for thousands of years by sheer instinct. Deny her the gentle embrace of warm arms that even a small rim of brain can recognize as safety. In the midst of all this advancement, we have come to value technological innovation, and the prolongation of life through invasive medical technology, more than we value human compassion and kindness. She is no monster, so why should she spend her final hours alone, like a pathological specimen, walled off from comfort in a little coffin of glass?

I think of the doctors of old, who gave us the word monster. It comes from the Latin word monere, from which we derive the English word demonstrate. It means “to warn.” For centuries, priests, physicians, and philosophers alike believed that babies like Luz were omens and signs sent from the gods. What else, except divine anger over human folly, could account for such tragic little bodies, broken before they could even be born?

And yet, far from being regarded as mistakes, these babies were an important part of the natural order. There was a perfection hiding in the otherworldly shapes of their uncommon bodies. There was a God who, with time and care, fashioned their physical flaws to point perfectly to our spiritual ones. And if one looked closely enough, a baby like Luz had the power to teach, instruct, and correct. Even in her short life, she could be a guide, bending us forcefully toward our own better nature.

Margaret Wardlaw (MD, PhD) is a pediatrician. Her writing has appeared in US Catholic, The American Journal of Bioethics, and Feminist Approaches to Bioethics. Her research and clinical interests include medical ethics, disability, and the care of children with medical complexity.

Read an interview with Wardlaw here and browse more real-life Frankenstein stories in Creative Nonfiction’s Spring 2018 issue, Dangerous Creations.