Scientific jargon is funny thing. Within a given field, it allows scientists like myself to be precise and succinct. But to outsiders it’s like a foreign language, and to non-scientists, it can even be more daunting. Take my work, for example.

“I investigate how cortical activity of the sensorimotor system reflects differential contribution of feedforward vs. feedback mechanisms during object grasp and manipulation.”

With enough time and critical thinking, most readers might unlock this description, but it’s not immediately comprehensible. Nonetheless, scientists have a long history of using jargon. And as long as we’ve been using it, we’ve been struggling to keep it in check.

We’ve all heard the phrase, “Give me the dumbed-down version.” It likely references the well-known “For Dummies” book series started in the early 1990s. Under distinctive yellow covers, these books examine a broad range of subjects, from home repair to complex physics. And when we’re not making our work accessible “for dummies,” we’re explaining things that “our grandmas can understand” or “breaking it down Kindergarten-style.”

While these expressions are thoughtful reminders to be wary about word choice, they often have a secondary effect too: they support a belief that the non-specialist audience knows very little. That they are, in fact, dummies. Of course, gauging your audience is a crucial first step in starting any explanation. But knowing when to shift the level of detail is the challenge, and in my experience, we scientists frequently miss the mark. Especially when we start with the mindset that the listener is unlikely to understand, there is a temptation to describe complex issues in simplistic, reductive ways.

I’m sure every scientist can relate to a moment when you’re asked a difficult question in a classroom, at a public event, or sitting around the dinner table. Your gut reaction might not be to clarify all of the scientific intricacies, but rather to stick to the basics. You make a snap judgement that the basic answer is the best way forward, leaving jargon entirely behind.

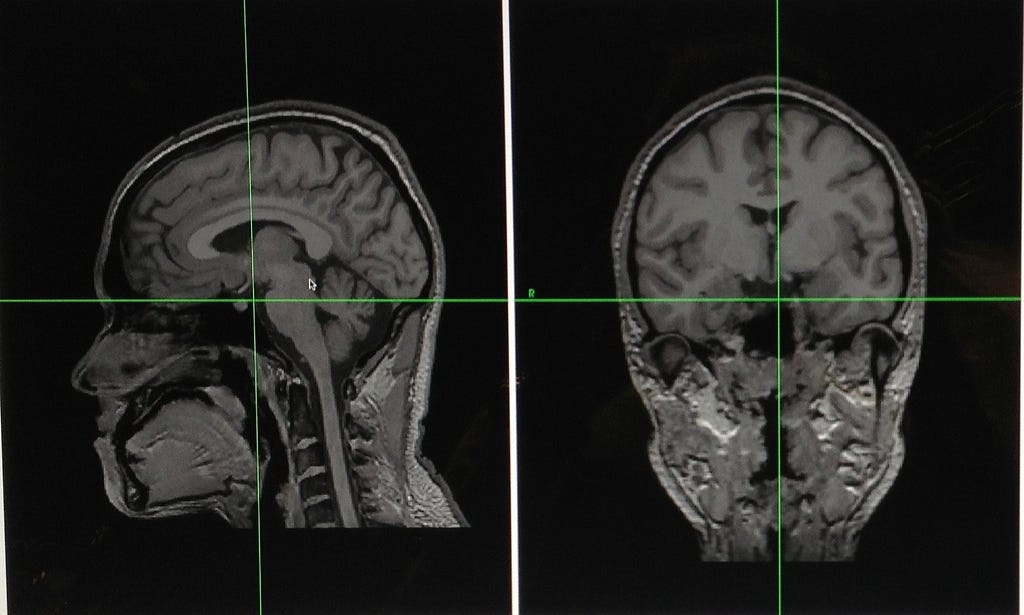

“I study how the brain controls the hand.”

That’ll do, right? Well, sort of. While this very basic answer is correct, it misses the true importance of the work: the details that show both our knowledge and passion. As scientists, we’re not just trying to better understand some part of science. We’re exploring new frontiers and trying to discover something important that no one has ever glimpsed before. The basic answer loses that core purpose. That question of value, of discovery. The scientific merit.

Missing the value of a scientific endeavor can have consequences. Scientists not engaging in thoughtful scientific conversation may make the public feel further estranged from science. In many cases, the people doing the asking are intelligent and capable of understanding complex topics if the information is delivered in the right way. And if that delivery is unclear or seems trivial, it may cause that person to feel that scientific topics are out of reach, or even valueless. The decision not to work hard to communicate science effectively, without flattening and simplifying it to death, exacerbates a chasm between science and the public.

This same pattern of miscommunication can easily be replicated in conversations with people who influence science at an institutional level, like grant reviewers, politicians, and policymakers. And it’s here that a misunderstanding of scientific merit can be critically detrimental. If no one can understand the value of a particular research project, then why allocate resources to support it?

I’m not saying we should stop trying to simplify our conversations. We deal with some really technical and complex topics, and so it’s a requirement for the job. What I am suggesting is that we never dumb down. And we never make assumptions about the listener’s ability. We simply need to pay more attention to the way we describe complex topics. Of course, we’ll need to surrender a little bit of concision. But if we only have to add in a sentence or two to set the stage for a given topic, it can be a worthwhile endeavor.

“When humans lift an object, like a full cup of coffee, the brain relies on different processes. These include both a memory of the cup’s properties from previous lifts, and real-time sensory information, like vision, to ensure we don’t spill or drop it. I study how the brain uses these two mechanisms during object grasping and aim to discover the brain areas involved.”

So, how do we do communicate effectively? Fortunately, this question has generated growing attention in recent years. There are readily available online resources like upgoer5 and read-able.com, which provide instant feedback of how complex your language is. Meanwhile, groups like the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science have expanded this cause to the university level, providing dedicated training to improve the way scientists communicate.

The content of every conversation, news story, or interview leaves an impression. And at the end of the day, being more cognizant of how science is valued and understood will help scientists to better write and speak at the right level for scientists and non-scientists. We’ll prevent the need to “dumb it down” or to rethink how to explain it to our grandma. We’ll start out the conversation on the right track from the start and share that all-important scientific merit. When scientists hit that mark they can inspire diverse audiences, and that’s where the magic happens.