The most beautiful emotion we can experience is the mysterious. It is the power of all true art and science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead.

–Albert Einstein

Our neocortex is very adept at automation — at habitualizing complex behaviors and routines of thought. Consider: how much of your day is patterned? How much of your thoughts are processes you’ve repeated before? A lot! And this is a good thing. Automation frees up our minds for the good life, the life examined, the life of the mind. Because I don’t have to concentrate so much on the complex neurological and physical act of walking to lunch, I can daydream into existence this blog post, for example. On the other hand, automation often lulls us into the predicament of predictable points, all strung together by the dull thread of everyday life. Negative emotions result. The poop emoji gets a lot of play.

Of course, it’s not all bad. Happiness abounds. Our lives are replete with opportunities for joy. Lessons from positive psychology elucidate the many “positive emotions” that elevate our lives, including love (of course), gratitude, inspiration, and amusement. And the last — amusement — is big business. Experience designers of all stripes focus on amusing users. Designing for delight is considered a surefire way to get users hooked. Amusing digital experiences, it goes, promote habit-forming products. Win! But wait. I was hoping to leverage positive emotions to alleviate the dullness of our habitual brains, not exploit them! Poop emoji.

There is another, rather unique, positive emotion — one that weaves through religion and history, art and philosophy. It is by nature fleeting, but nonetheless essential. It is awe, wonder, amazement. Situated “in the upper reaches of pleasure and on the boundary of fear,” awe is defined by psychologists as “the emotion that arises when one encounters something so strikingly vast that it provokes a need to update one’s mental schemas.” When we are facing the unfathomable, standing, as Einstein says above, “rapt in awe” by the Grand Canyon, the sky-long sweep of the Milky Way, or the opening scene of Lord of the Rings, our eyes widen, our mouths go slack. Our heart rates actually decrease in these moments. This isn’t fight or flight; it’s stay and be amazed.

Recent research has uncovered more about awe. Experiments reveal that time slows down for those experiencing wonder; subjects who recently experienced awe felt they had more time available to them, that they had more room to breathe. This particular study found that the recently awed subsequently experience an increase in the ability to develop new ways of thinking about the world, more willingness to engage in prosocial behavior, and a greater desire for experiential, rather than material, goods. Now THAT is a positive emotion. Delight gets you hooked (on products, experiences, revenue streams). Wonderment gets you unhooked (from self-absorption, time starvation, status quo schemas). Delight is a kiss on the cheek, a cheap thrill — game over, please insert quarter. Awe is what it is to be alive.

So let’s design for wonder. There is awe-inspiring digital now, of course. Many games do this. VR. Positive psychologist and design researcher Pamela Pavliscak also identifies awe in digital’s big picture: she explained in an email that it can be found in “…the scope of human response to a tragedy on Twitter, or when we connect with someone using an app like BeMyEyes. This is wonder for the digital age.” More please! I’m sure it’s profitable. Awe can be big business too. In my digital future, digital thaumaturges will amaze the masses. Heck, 4.5 million people visited the Grand Canyon in 2013.

As AI, connected things, and ubiquitous computing unfold, let’s get deeper than delight. Let’s teach the robots poetry and design for awe as well as joy. We wouldn’t want Skynet, born of our ruthless pursuit of good click-through rates and addictive interfaces, to come to agree with Einstein’s sentiments.

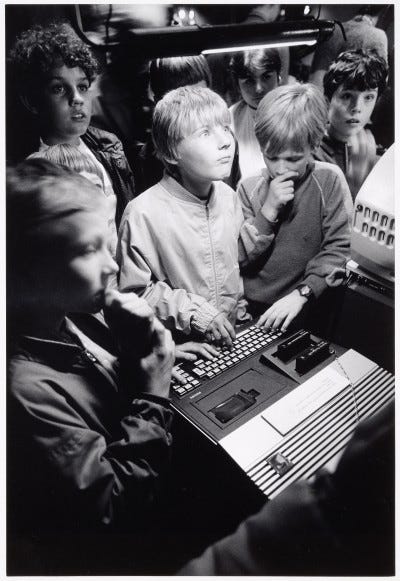

Image: Computerfestival De Meervaart, Michel Pellanders, 1984, photographic paper, h 50.5cm × w 34cm. More details, © Michel Pellanders. Used courtesy of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

To learn more about the Center for Science and the Imagination, visit our website.