Our stuff is meaningful; it’s symbolically and semiotically imbued with signals of memory, utility, and identity. These meanings are the fabric of culture — shared ideas and values that we acquire as members of society. They exist as thoughts we carry in our skulls, thoughts triggered when we consider or encounter our things. This symbolic capacity provides the mental metadata our neocortex is wired to bear and society is arrayed to share.

When we perch digital objects like our Instagram pics and YouTube videos, they accumulate a truly novel dimension. This is an accretion of comments, likes, search affinities, and what computer scientists call descriptive or guide metadata. Defined on Wikipedia as “usually expressed as a set of keywords in a natural language,” this metadata is a persistent halo of co-creation hugging our digital objects. And all this is fundamentally different from the cortical-cultural metadata associated with our regular stuff described above. Unlike mental metadata, digital tags and comments streams exist “out there” and are more readily bound to digital objects. It’s as if our myriad thoughts about our favorite chair were pinned to its cushions on little slips of paper.

The hashtags on my Instagram account are expressions in the same genre; they are whispered asides to the machine, complete with a silent “#” prefix of computer (vs. human) code. Hashtag machine slang has even migrated into our human-human communications; hashtagged metadata works as paralinguistic commentary in tweets or can even be found in speech. Jimmy Fallon and Justin Timberlake’s commentary on this practice is #flawless.

Either way, hashtagging originated as a way for us to write to machines. This notion is not all that crazy. Consider the observations of Jaron Lanier at the outset of his book You Are Not a Gadget:

“…these words will mostly be read by nonpersons…[they] will be minced into atomized search-engine keywords within industrial cloud computing facilities located in remote, often secret locations around the world.”

The robots may in fact be our most avid readers!

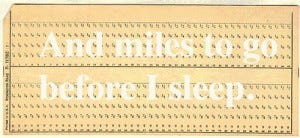

Let’s take this a bit further. What if we combined Lanier’s observation with our intentionally robot-facing metadata authoring. What if a video or photo stock site were to partner with poets who composed poems inspired by and forever associated with each image asset? The primary audience for these works is the robot — the search algorithms are enhanced by the rich poetic content. Users could search using more expressive and less direct terms and achieve robust results better attuned to their longing. Of course, the poetry can be read in its own right. It may even accumulate its own metadata. But that is secondary. Primarily, this is poetry for robots.

In this instance, poetry is enriching the digital object’s online identity, findability, and utility. Users could browse the collection by broad and poetic search terms like “the inky night” and “hair like a small fog.” This elevates authored metadata and reveals its true form.

We are already composing metaphorical descriptions of our experiences and objects and people all day long. It’s called thought. “Metadata” is a computer science term for something that, when generated by people at least, is deeply human. It’s a form of persistent linguistic description, a tangible act of associative thinking, a bridge, a love note to the future. This, happily, is a fair definition of poetry as well.

To learn more about the Center for Science and the Imagination, visit our website. Or write a poem for a robot.