Talking Science Fiction and Game Design with James L. Cambias

James L. Cambias is an award-winning science fiction writer and an accomplished designer of role-playing and tabletop games — as well as a collaborator on our Project Hieroglyph, for which he wrote a short story, “Periapsis.” He sat down with us for a conversation about his journey into the gaming world, how to create compelling games that incorporate real science, and the stories and games that inspire him most.

Joey Eschrich, Center for Science and the Imagination: Could you tell us a little about yourself and your work?

James L. Cambias: I got my degree in the History of Science at the University of Chicago. My writing career started with role-playing game articles and source books in the 1990s, and I wrote role-playing games throughout the 1990s and worked for a couple of local newspapers in towns that I lived in. I sold my first short story, “A Diagram of Rapture,” to Gordon Van Gelder at The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction in 2000. I continued writing short stories, and I sold my first novel, A Darkling Sea, three years ago now. My second novel, Corsair, came out in May 2015. The primary activity in science fiction used to be short stories, but now it’s novels. That’s the big show.

JE: What motivated you to get into role-playing games and tabletop gaming in the first place? Was it something you were always passionate about?

JLC: This is a case of monetizing my hobby. I played RPGs all through high school and college, and I had one of the first Dungeons & Dragons editions — it’s called the Blue Box among the insiders. I also had the first mass market edition of Dungeons & Dragons and first editions of a lot of other role-playing games because I bought them when they came out and never threw them away.

JE: What’s favorite game that you played when you were young — something that shaped or inspired your work?

JLC: The game Call of Cthulhu from Chaosium, which is an H. P. Lovecraft RPG. It’s one of the more influential games out there, and it certainly influenced me in a number of ways. For example, I’m not sure if I would have majored in the History of Science had it not been for that. I went to college intending to be a physicist, but that turned out not to be for me. During my second year of Physics, I switched my major to History of Science, and I suspect some of the stuff I had run across in Lovecraft primed me for that.

JE: How do you think your History of Science degree has influenced your work? What skills from that field have helped you out?

JLC: I don’t know that it did, to be honest. I think it’s more a reflection of having the kind of mind that likes to know about a whole bunch of disconnected or hard-to-connect things. So being interested in the history of science meant I was the kind of person who would be interested in writing a 120-page book about Mars for a game company.

JE: Okay, so you were involved in this game design world as a critic and as a creator. Why did you decide to finally found your own company, Zygote Games?

JLC: It was the idea of our business partner, Joseph Steig, who had two sons with Pokémon cards. And the younger one, in fact, was not even old enough to play the Pokémon card game, even though it’s aimed at fairly young players. He couldn’t really play the game following the rules, but he knew the names of all the characters and what their abilities were. And Joseph wondered, “Why can’t kids learn about real animals and real living things this way?” So he got together with my wife who is a biologist and myself, as a game designer, and we worked up a game, which we thought would be really interesting and educational. That’s how Zygote got started.

If I have design philosophy, it’s that the gameplay should actually reflect whatever it is you’re trying to educate people about, rather than just creating a game that has the “chrome,” as we call it — all surface appeal with no substance.

JE: How is it to work side-by-side with a scientist in developing these games? How does that process work?

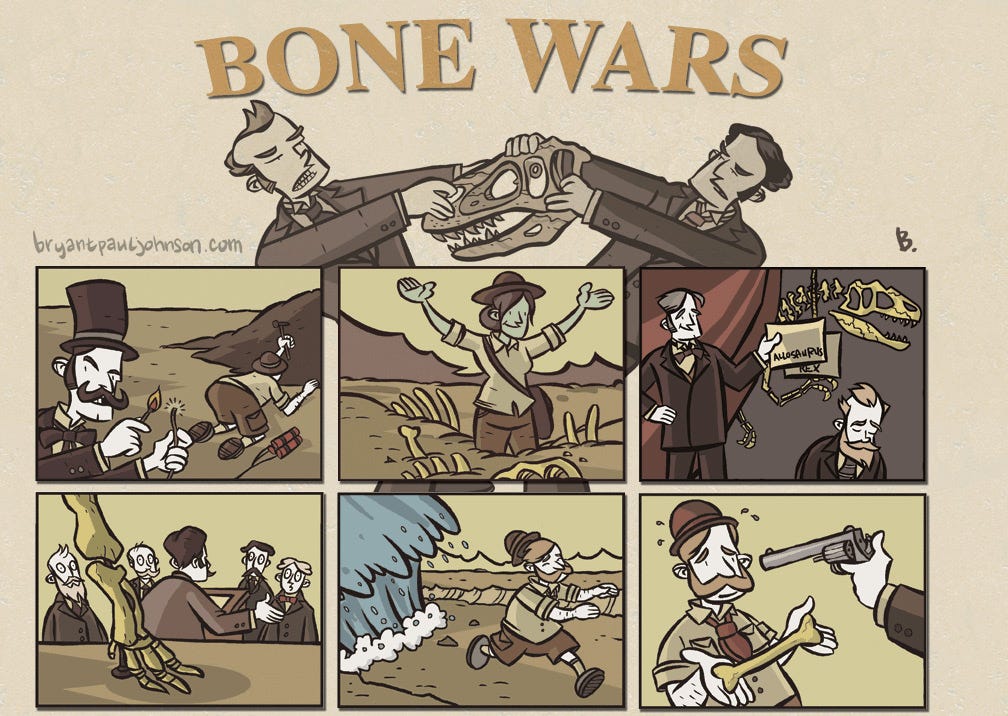

JLC: With the game design work I focus on game mechanics and my wife focuses on the science part, that being what she does. So, for Bone Wars — a game about dueling paleontologists during the “Dinosaur Rush” in the 19th century — she did all the research, she made sure that our dinosaur information was as current as possible.

JE: Is the process of building the world different if you’re working on a novel versus working on a game?

JLC: For me, absolutely not. They have absolutely the same process. That’s the one area where role-playing and fiction writing really overlap: the background. In both cases, you’re trying to build a background that’s plausible and convincing, but also serves as a platform for interesting stories. It’s the storytelling where they diverge, because RPG stories follow a very different structure from fiction novels or short stories. RPG characters also tend to incrementally improve, so the long-term plot arc is of these people gradually becoming more powerful and successful — whereas in a novel, ideally you start with someone powerful and successful and ruin his life and then show his recovery.

JE: What’s your favorite game that you’ve worked on?

JLC: The game that probably plugged into my head the best was a game from Game Designer’s Workshop by Frank Chadwick called Space: 1889, which was steampunk before steampunk existed. It’s a Victorian science fiction role-playing game. That was one of those cases where it turned out there was a hole in my brain exactly the shape of the game.

JE: Do you think that RPGs, which encourage deep engagement from the player, have the potential to help people think more carefully and sensitively about other people’s experiences?

JLC: I’ve talked with people who use games in education and one of the things they do is run role-playing scenarios set in specific time periods, as a good way to play tourist and to encourage the players to think in the ways that people in that context would have thought. I think that approach is very good for encouraging people to try to take a different perspective.

But those are usually specifically in the form of educational games where your history teacher says, “Today we’re going to do this role-playing scenario where you’re all abolitionists trying to help the slaves escape from the South,” or something. But when people buy a commercial RPG, they’re buying entertainment and that’s the primary goal. And you’re going to be running a risk if you’re sacrificing entertainment value for an educational agenda.

JE: Looking back at your career so far, what story has inspired you most? What novel or short story do you look to as an aspirational or inspirational moment?

JLC: In terms of science fiction novels, I guess what I would really aspire to — if I could write that well — is pretty much anything by Tim Powers, but in particular his supernatural spy novel Declare. It’s an amazing piece of craftsmanship because he’s able to weave a supernatural spy thriller around real events in the life of a real spy, Kim Philby.

JE: So, last question: as a game designer, what’s a game that you wish that more people knew about and that more people would play?

JLC: Greg Costikyan’s original Star Wars role-playing game from West End is a real work of genius. He was one of the first game designers in the role-playing field to realize that the game doesn’t have to be realistic in terms of the real world. It has to be realistic in terms of the fictional world it’s replicating.

So in his Star Wars role-playing game, what works in the real world is not as important as what works in Star Wars. How do you replicate the experience of the characters in the Star Wars films, rather than what we perceive as realistic? Of course, a lightsaber would be a terribly impractical weapon, but we’re playing a game in which people wield lightsabers. That’s an RPG that I think is one of the best, and it deserves more credit than it gets.

To learn more about James L. Cambias and his work, visit jamescambias.com. His short story “Golden Gate Blues” was recently published in the March/April 2016 issue of the Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction.