One of the more terrifying diseases to appear in the last few decades is mad cow disease, scientifically known as bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE). Unlike some other diseases in which the more you understand, the better able you are to cope with the concept, the more you understand about mad cow disease, the more terrifying it becomes. This disease is a fatal brain disorder that is neurodegenerative, meaning it causes degeneration in the brain and spinal cord. The incubation period for BSE ranges anywhere from 30 months to 8 years, and it is transmissable to humans, though the form of the disease humans contract is called “variant Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease” (vCJD).

This subject may seem an unlikely one for poetry, but then again, what is poetry if not a medium for discussing your deepest fears or exploring something from a new angle? In her poem “The Mad Cow Talks Back,” Jo Shapcott writes from the point of view of the mad cow herself, relating what Shapcott imagines the disease might be like:

I’m not mad. It just seems that way

because I stagger and get a bit irritable.

There are wonderful holes in my brain

through which ideas from outside can travel

at top speed and through which voices,

sometimes whole people, speak to me

about the universe. Most brains are too

compressed. You need this spongy

generosity to let the others in.

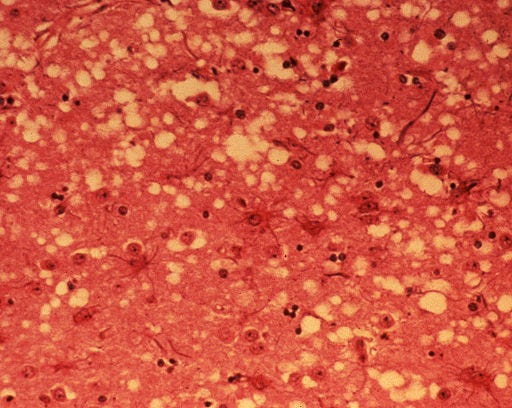

This first stanza describes the main effect of the disease: an infected brain is so filled with holes that it resembles a sponge.

But what causes this disease, with its bizarre manifestation and fatal diagnosis? Why is it transmissible to humans at all? What can we do to prevent it?

Unlike most other illnesses we are familiar with, this one isn’t caused by a bacterium or a virus, or even a parasite. Rather, the cause of mad cow disease and all other diseases of this type (called transmissible spongiform encephalopathies, or TSEs) is a prion. A prion is a misfolded protein that causes other proteins to fold incorrectly. That’s right: an infectious protein. The strangest thing about a prion is that, unlike all other known infectious agents, it does not contain any nucleic acids (DNA or RNA).

Infection occurs when a prion enters a healthy organism and induces normal proteins to fold into prion form. The resulting structure is extremely stable and resistant to denaturation, a term used to describe a protein unfolding and losing structure as a result of chemical or physical agents. These sturdy misfolded proteins aggregate into plaques, which cause the infected cell to die, leaving a hole. The prions are then released to infect surrounding cells.

Since they don’t have any genetic material, prions aren’t alive, and so they can’t be killed. Measures to sterilize contaminated meat are extreme: incineration at 1000 degrees C (1832 degrees F!), autoclaving at 134 degrees C, boiling in lye for 15 minutes, or exposure to concentrated bleach for over an hour. Since you can’t “kill” or deactivate prions by cooking or freezing, the best prevention is to completely avoid potentially contaminated meat. To this end, the USDA has tightened restrictions on tissues known to carry mad cow disease (brain and spinal cord tissues) and has banned “non-ambulatory” cows (those that can’t walk) from being processed for human consumption.

So, the progression of disease: a cow becomes infected by a prion, most likely through its feed. Prions get into the bloodstream and cross into the nervous system. Once in the nervous system, clumped prions kill the nerve cell, and the prions are released to infect surrounding cells. Numerous nerve cell deaths lead to loss of voluntary muscle movement and to abnormal behavior, including increased aggression and excessive reactions to noise or touch. Eventually, the cow can no longer walk, and dies. Perhaps, as Jo Shapcott envisions in her poem, the brain goes so quickly that the cow doesn’t realize the horror of its situation. Maybe the infected cow simply experiences things in a different way. Although it’s hard to imagine, we can allow her poem to give us hope that these unfortunate animals don’t go so harshly. The cow tells us in no uncertain terms:

I love the staggers. Suddenly the surface

of the world is ice and I’m a magnificent

skater turning and spinning across whole hard

Pacifics and Atlantics. It’s risky when

you’re good, so of course the legs go before,

behind, and to the side of the body from time

to time, and then there’s the general embarassing

collapse, but when that happens it’s glorious

because it’s always when you’re travelling

most furiously in your mind. My brain’s like

the hive: constant little murmurs from its cells

saying this is the way, this is the way to go.

This post originally appeared on the I Spell It Nature blog.